VIFF documentaries sketch in the history of B.C. art icons

The Painted Life of E.J. Hughes reveals quiet life of a master who avoided spotlight; The Art of Adventure tracks a young Robert Bateman’s journey with Bristol Foster across the world in a Land Rover

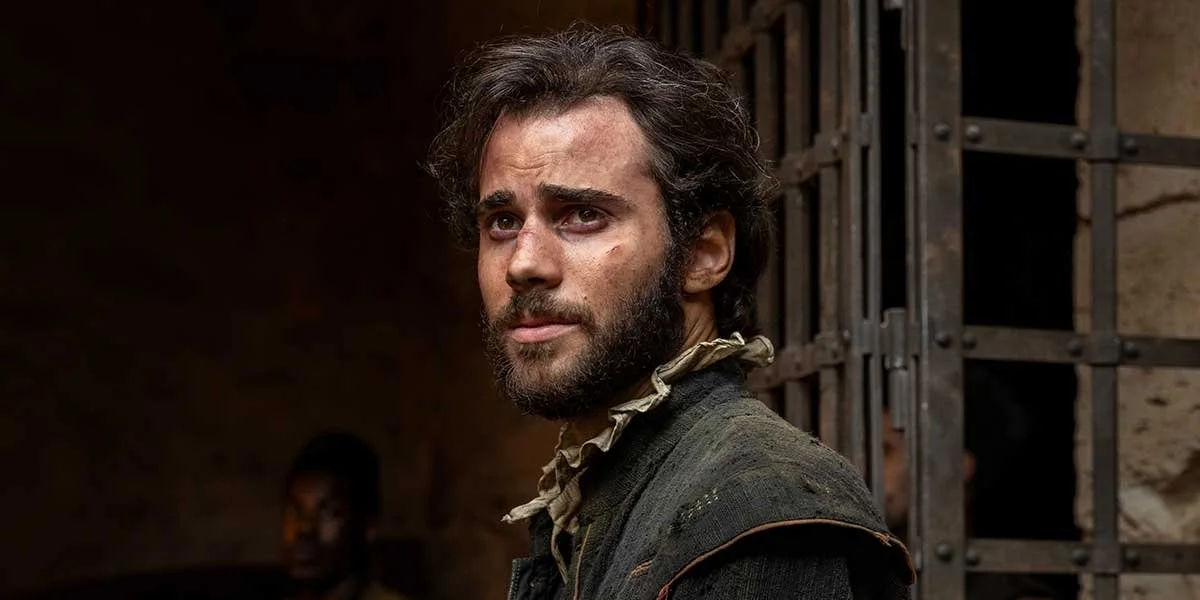

Robert Bateman and Bristol Foster in the Grizzly Torque in India, in The Art of Adventure

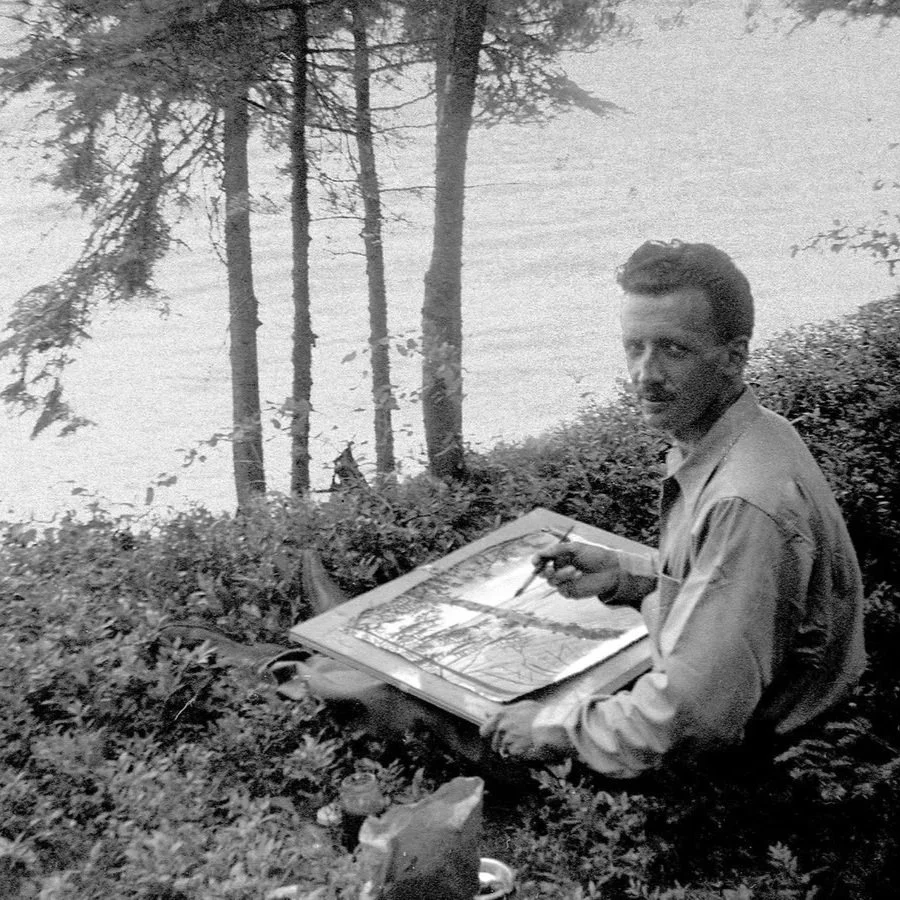

The Painted Life of E.J. Hughes

The Painted Life of E.J. Hughes screens October 4 at 6 pm at SFU Woodward’s and October 7 at 3:15 pm at Granville Island Stage (both with Q&As), as well as October 8 at 10:30 am at VIFF Centre and October 11 at 3 pm at VIFF Centre; it also opens the New Westminster International Film Festival October 24 at 6 pm. The Art of Adventure screens October 5 at 3 pm at Vancouver Playhouse, October 7 at 6 pm at Granville Island Stage (both with Q&As), and October 12 at 11 am at VIFF Centre

TWO DOCUMENTARIES seeing their world premieres at this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival reveal compelling new sides to a pair of famous B.C. artists.

The Painted Life of E.J. Hughes tracks the late icon’s journey from struggling to make a living working fishboats during the Depression to becoming a war artist in the Second World War to coveted collector status in his 80s and 90s. Alison Reid’s The Art of Adventure, meanwhile, follows wildlife artist Robert Bateman and Bristol Foster’s 60,000-plus-kilometre journey on a Land Rover through the African savannah, over the Ganges on a rickety boat, and into the Australian Outback. It ties the voyage into their ongoing ecological activism today, as nonagenarian neighbours on Salt Spring Island.

Both documentaries draw on rich historical archives, giving art fans a detailed understanding of two painters with deep connections to the land. One lived a modest life until old age, when his iconic images of coastal B.C. were finally celebrated at auction houses. The other, as The Art of Adventure reveals, is still enjoying widespread popularity outside of full acceptance by the fine-art establishment in Canada.

UNCOVERING A QUIET LIFE

TO MAKE The Painted Life of E.J. Hughes, Vancouver director Jenn Strom spent five years criss-crossing the coastal communities of B.C. and digging into the life of a shy artist who avoided the spotlight. Helped by B.C. biographer Robert Amos and a treasure trove of old taped interviews, she finds an intensely private man who dedicated his life to the meticulous work of painting, and who was devoted to the wife who supported him.

“What’s so special about his artwork is you really can’t separate the fact that he was such a highly sensitive person who needed all this alone time—that exquisite sensitivity he had is what made him the artist he was,” Strom tells Stir. “There’s just this incredible archive of his life, and because he was such a private person, there was this real balance of trying to be very respectful and honour that.”

Together, Hughes and his wife Fern led a quiet life at Shawnigan Lake, spending years without a car at their rural house, walking a long route each week to get groceries. In some of the film’s most moving moments, they also faced personal tragedies.

“She was the love of his life and I wanted to honour her,” Strom explains. “She was his support person—and part of this to me is to really look at what a creative soul needs in order to be able to do their work I’m always interested in unpacking what creativity is and how it works.”

Some of Strom’s favourite archival photos in the feature doc were taken by Fern. ”There’s something about when someone you love is taking your picture. You have a certain kind of expression, right?”

One of the highlights for Strom was discovering the Doghouse, the Duncan family restaurant where Hughes ate every day in the last decade or two of his life—mingling servers who got to know him well and gifting the eatery with a wall full of paintings.

Hughes’s colourful, almost dreamlike coastal paintings fill the screen throughout the film; interviews with prominent Canadian art historians and former curators Ian Thom (Vancouver Art Gallery), Charlie Hill (National Gallery of Canada), and Laura Brandon (Canadian War Museum) deepen the appreciation of works by a man who often didn’t attend his own, late-life retrospectives.

Filmmaker Jenn Strom travelled B.C. finding the views in E.J. Hughes’s paintings.

“He didn’t change himself to go towards what was popular,” the filmmaker observes. “He kept doing what he found beautiful. And in the end, his deep perseverance and his work ethic—this one person just doing his thing alone in a studio—left us this incredible treasure trove that I think reminds us, in some cases, how green places were, or what the historical industry was there, or what the cultural presence was there.”

With books of Hughes’s famous images in hand, Strom travelled through B.C. trying to find the places he’d painted. Some of those viewpoints, like Dawson’s Landing, were reachable only by boat, and others had all but disappeared due to development.

“It was one of the more fun parts of the film,” Strom says. “I’ve gone all over Vancouver Island and Gabriola Island and up to the interior to Revelstoke and Chase, to Chilliwack, the Fraser Valley, and most exciting for me was actually getting up to Rivers Inlet.”

For one famous image of a Comox Valley hayfield, she spent days driving around Courtenay trying to figure out the perspective.

“That whole area is now houses and suburbs, and you’re kind of driving up and down hills and trying to figure out where that view lines up. I sort of narrowed it down to this house that was being built, and I kind of see the view you know from beside it. I finally parked, and when I knocked on their door, I could see that they were home, still doing some finishing work in the garage, and this woman opens the door. I’m like, ‘Hi I’m making a film about E.J. Hughes,’ and she just says, ‘We have the view.’”

Adds the director, who clearly has a deep affection for the late artist and the places he painted: “I would absolutely recommend anybody to grab these books and set out on a little scavenger hunt to try and find these places.”

INTO THE WILDS

TORONTO-BASED FILMMAKER Alison Reid, the director behind the award-winning doc The Woman Who Loved Giraffes, met Bateman and Bristol on a vacation to Salt Spring Island. When the director and former stuntwoman heard the almost unbelievable story of their life-changing trip as young men, she became obsessed with centering a film around it.

Reid started shooting in 2021, beginning with interviews with the two well-known men on the Gulf Island, and drawing on the incredible archival materials from the trip she had at her disposal. Those included Foster’s Super 8 footage and Bateman’s extensive sketches of the Masai, wildebeest herds, and exotic birds—many of the Bateman’s journals set on the glovebox of their Land Rover while Foster drove.

What struck Reid so profoundly was how you couldn’t do the same trip today—not just because of geopolitical barriers but because of human encroachment. As Bateman suggests in the film, the two were witnessing an untouched nature that was disappearing even as they were immersed in it.

Alison Reid

“All the safety nets we have now were not there,” Reid marvels in a phone interview with Stir. “There was no, ‘Oh, we’re stuck in the mud. Pick up the cell phone’. But, you know, they did have to be self-reliant—and at the same time, they felt so free doing that.

“You couldn’t have the experiences that they had today,” she continues. “And it would be totally different. They experienced something when the world was a lot less unscathed than it is now. It really is an incredible record of the way the world was.”

The Art of Adventure follows the Canadian eco-icons as they form a lifelong friendship as teens in Toronto’s Junior Field Naturalist Club. In 1957, when Bateman is a high-school teacher and Foster is between his master’s and PhD in Ecology, they decide to take a 14-month hiatus to drive around the world—picking up their trusty Series I Land Rover, nicknamed the “Grizzly Torque”, at the Solihull factory in England before heading to Western Africa by freighter.

Then, incredibly, they drive from Ghana through Central Africa to Mombasa, then take another freighter to Bombay, crossing to Calcutta and head on to Australia. Foster captured a stunning document of the trip on 16mm film footage—including scenes of the pair using a capstan winch to pull the Grizzly Torque out of the East African sludge to their first sights of wildlife roaming the Serengeti savanna and fascinated tribes gathering around their vehicle. Remembering entering the Great Rift Valley in the film, Bateman calls it “as close to Paradise as I think I’ll ever get”, marking the beginning of a lifelong love affair with the Serengeti’s animals and birds—many of which appear in his most famous prints and paintings today.

Reid interweaves those adventures with the decades that followed, when Bateman rose to become a famous Canadian wildlife painter and Foster established himself as a prominent B.C. biologist who headed up this province’s Ecological Reserves program and helped set aside more than 100 areas for research.

Late in the film, the director addresses the uneasy relationship Bateman has as a realist wildlife painter with the fine-art establishment. Today, for example, none of his work hangs in the National Gallery of Canada collection.

“It’s an incredible injustice,” Reid asserts. “Canada has awesome people, accomplished people, talented people, and let’s elevate them like the Brits do, like the Americans do—there’s nothing wrong with celebrating our own and bragging about our own.

“You know, Bob’s jam is doing that realism,” she adds. “And from what I understand, wildlife artists are ghettoized—they aren’t held in high esteem in the art community for some unknown reason.”

Ultimately, though, this is a story of two nature lovers whose story, Reid hopes, will send a message to a new generation that has come through a pandemic—and often experiences the world through screens: “Just go out into the world”.

“That’s what Bob and Bristol want,” Reid says. “They want people to reconnect with nature—and that’s so important for mental health...and to make people inspired to connect with the environment, to protect the environment. Like Bristol said at the end of the film, ‘If you’ve got a dream, don’t hesitate. Do it.’” ![]()